Since the 60’s innovation, research has stagnated to almost zero because of all the bureaucracy that hampers focus, risk taking and yield quality. That’s one of the very poignant points of this wonderful video by physicist Sabine Hossenfelder. Not only does bureaucracy stagnate innovation, but also research, productivity and real breakthroughs. And there ironically is great research to back up those claims! I think this applies to design as well.

Before we go into this in great depth, make sure to check out Sabine’s video. Perhaps you glean other insights from this than I do with my perspective.

My take away is mostly two fold:

- Since the sixties innovation and research have been coasting on breakthroughs that were made in the decades right after the war.

- Apparently the biggest driver for this is a lack of long tail research because of the nature of funding and perhaps even more importantly: a lack of urgency.

This is not perse awful, because new things keep popping up every day at a seemingly higher pace, but what we make is academically derivative. We have been working on a long backlog of applied innovation and research. In other words: we have been proving and applying the theory incrementally.

From creating new to production for scale

I have seen these patterns first hand in digital design and technology. From the seventies to the nineties we have created new, original technologies that have literally created dozens of new fundamental industries. New industries like chip manufacturing via space technology, to web design. These industries have in turn disrupted and uprooted many other incumbent industries like marketing, mass communications, theoretical science, and law.

Nowadays, however, these new industries have become incumbents themselves. From inventing new patterns and creating new industries and causing real societal disruption, innovation and research itself went from ‘creation’ mode, to ‘production’ mode, or from wonderment to scaling, from discovery to optimization, from law-breaking to law writing.

This change has in a real way determined the trajectory of many of my peers. We were ‘done’ with proving, discovering, and connecting new patterns and designs. From the late 2000’s we found ourselves more and more in production mode, implementing the design systems, ‘user patterns’, and teaching these patterns as truths, rather than something that should be challenged. The cause for this is mainly the need for scale, how we made money and what is needed to create such production scale: rules, laws, predictability, in short: bureaucracy.

Bureaucracy killed creativity, and flexibility

The best way to show how research and innovation are hampered, erm ‘regulated’ by bureaucracy, is by showing the process one takes to fund their research.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtxjatbVb7M

As I could not find a research paper or image source, we’ll take the above example as an indication. But I have now tasted a bit of the processes in the government bureaucracy and the work style of organizations surrounding the government, and I have to say: this seems not at all strange or outlandish.

Having worked for customers that have to deal with governmental bureaucracy daily, but have a different function, let’s say delivering advisory capacity, they work like a bureaucracy themselves. Not only tailoring their products to fit the bureaucracy that asks for their services, but specifically limiting their executing power and product quality by mimicking the language, culture, range, and processes of their customers to a tee!

The partner companies of governments and therefore their bureaucracies seem to have become less capable of fulfilling the required services, by being a self-censoring extension, rather than providing an actual value add. The government in some cases might as well answer their own questions. Not only are incumbent partners slanted by knowing what answers might ‘work’ for their customers, they also have organized themselves to be highly compatible with the bureaucracy. This way, no other organization with sufficient funding can ever challenge their market, but even then, they and the government have taken themselves out of the chance to ever change that situation.

Creative industry getting no foothold in the government

This tailor-made solutions made by similar, highly bureaucratic organizations working for the government, make it nearly impossible to become a new player. Specifically for industries that are expected to be different, it is impossible to become a partner to the government, because of this fundamental conflict.

The conflict lies in that the creative industry yields its value from its connection with people and their behavior, which changes and is unknown and less predictable. The unknown is the question the creative industry is used to solve. A bureaucracy does not accept the unknown, it deals in certainty, and accountability, which in turn is built on predictability, partners, law, and in itself more bureaucracy.

In my view, the creative industry had cracked the need for conformance from the governmental bureaucracy and scalability from the market in and around 2015 to 2020 in a quite harmful way. They needed to become too big to ignore to capitalize in larger markets and did so in roughly two ways: private equity and acquisition.

Both investors and the mostly ICT-powered acquisition partners made the creative organization and their products scalable, lame, and very much compliant with governmental expectations. They were in! Or rather, the creative industry as it was known in the early 2000s did not exist anymore. It slayed itself into submission and left a creative gap in the landscape.

Necessity broke bureaucracy

So there we were in 2021, with a highly optimized and bureaucratic government and its compliant partners, faced with a huge challenge. A challenge where people needed to have access, information, and most of all: empathy to understand and cope with their small, new world. And none of this was available. The governments could not understand fast enough, act fast enough, and most of all: could not fathom what the question was they needed to answer.

Fortunately, some folks in the government took the mandate to develop answers. They tried to ask their ‘creative’ partners but found that their own rules, processes, and mindset were prohibitively limiting to getting answers in time. Their own rules to outsource and grant the projects to partner companies dictated timetables and vetting processes of several months, but time was of the essence. The answer was: to internalize the creative talents needed and break the bureaucracy so they could advise the unconventional, make what is needed, and rapidly improve along the developments.

This necessity laid the groundwork for new capabilities in the government that did not play to the tune of the bureaucracy but asked the bureaucracy to change itself so it could do its damn job. Quite a novel insight that unfortunately changed right back when the crisis settled down. Old patterns reemerged, the rules banned the creativity back into its bottle, and ‘order’ was reinstated. Nobody learned, and the ones that did were dispersed throughout the vast apparatus of the government.

Forcing necessity by emergency?

As our world is bound to change by new emergencies we see new players emerge in legacy industries. Think of the reinvigorated defence industry in Europe that feels like it needs to compete with the competition from both the east, south, and west! Similarly, the reinvigorated feelings of being self-sufficient stirred massive national innovation investments throughout the country and region.

The question that Sabine Hossenfelder asks her audience is quite poignant: do we need an emergency to be creative, innovative, and work on fundamental, long-term, risky research? Does the measure for success in our self-inflicted bureaucracy not blind us from what’s really propelling us forward, what’s making the difference, and what’s creating a brighter future?

I for one have suggested other, less abrupt changes to highly bureaucratic organizations like our government: Incrementally integrate both creation and production into the DNA of government and have bureaucracy support it, rather than dictate and limit it. To me, that’s what bureaucracy is always intended for maximizing positive outcomes. That means being cognizant of its limitations and being able to incorporate and give priority to the perspectives and values of others.

It’s just a model

Okay, I did not want to end this sappy, but it’s true. The government seems to have lulled itself and many of its compliant partners into a false sense of security through bureaucracy. They need to embrace that the unknown, unexpected, and unstoppable are not perse threats, but opportunities.

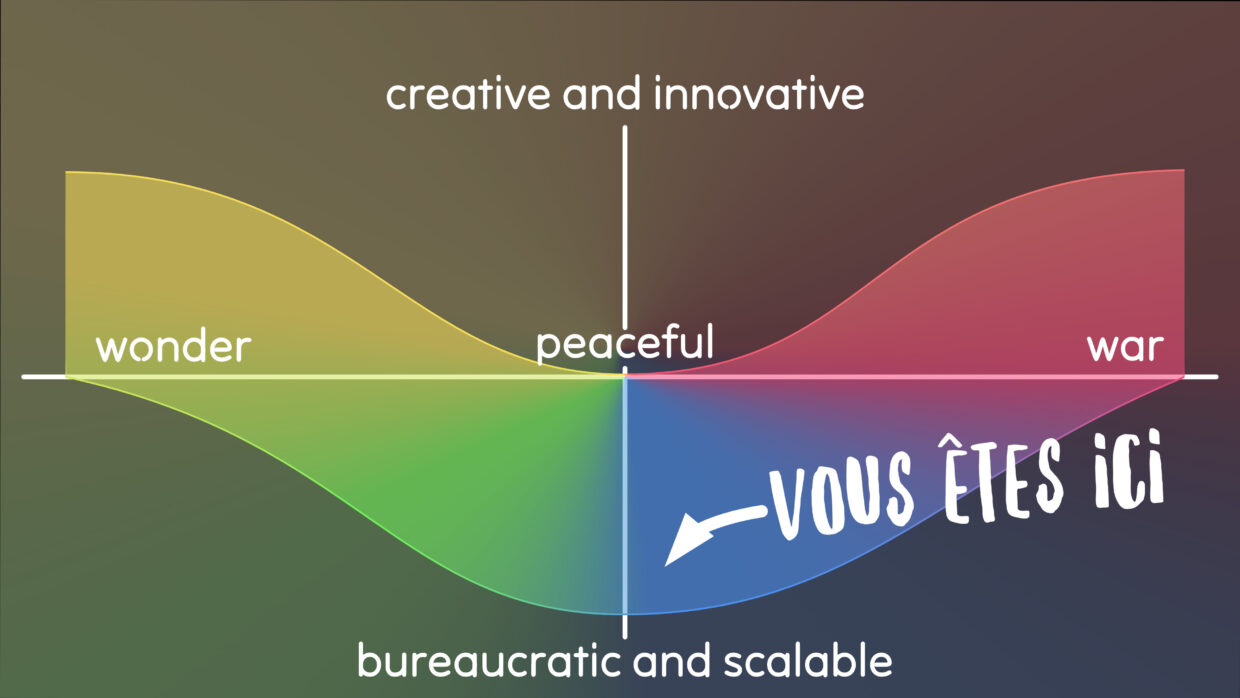

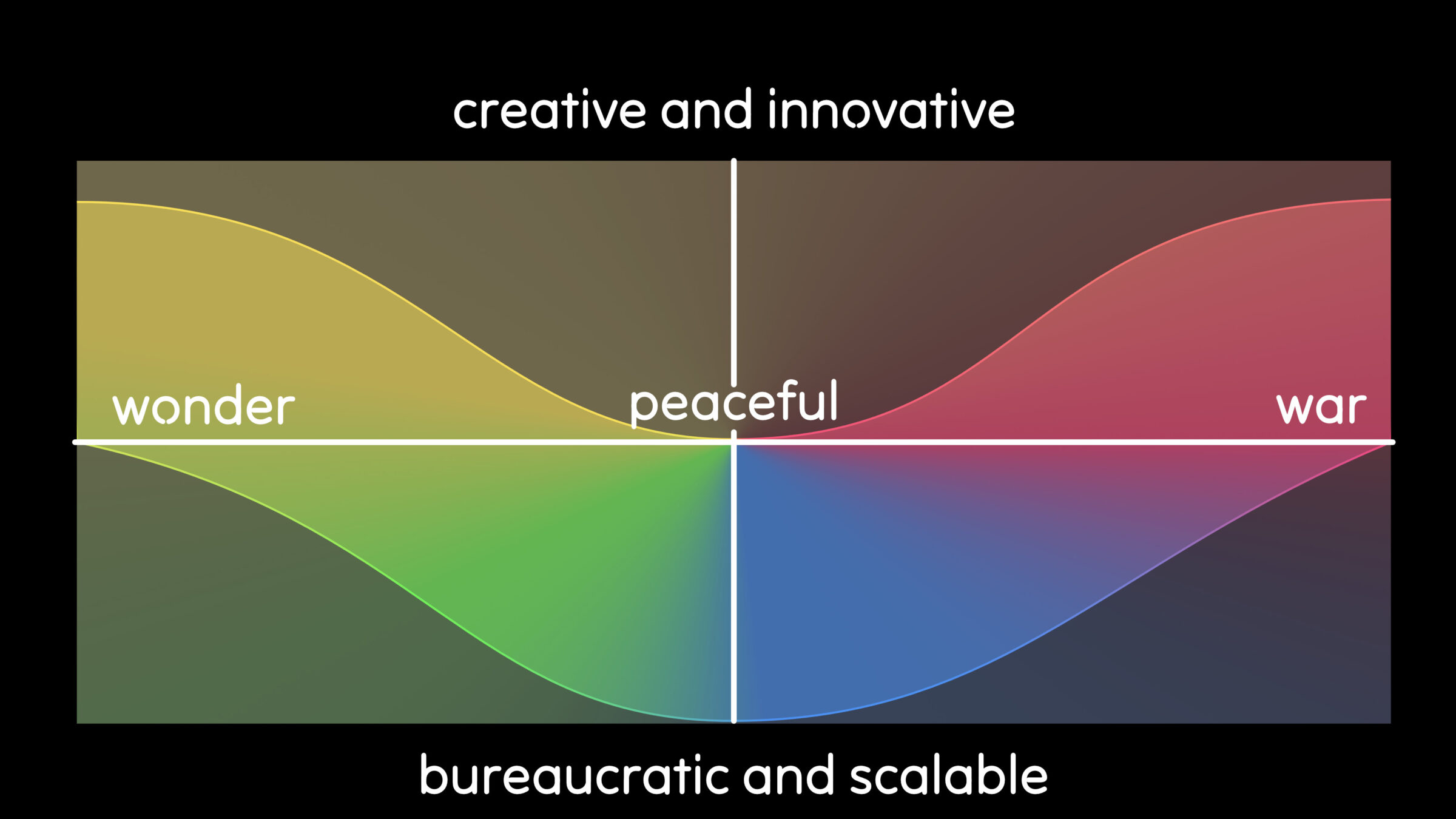

From one of my presentations: Adaptive cycles plotted on bands of creativity and bureaucracy

Finally, this all is a cycle. Our society and governmental behaviours are similar to a company in a very long cycle where we travel through phases of wonder, peace, and war (S. Wartly: https://blog.gardeviance.org/2014/04/from-a1-to-a6.html). In these phases, we see stages of instability and high-velocity innovation and creativity and phases of consolidation, bureaucracy, and safety (Adaptive cycles: http://besurbanlexicon.blogspot.com/2013/05/adaptive-cycle.html Ginderson and Holling).

Let’s be cognizant of these cycles, so we can navigate our way through the landscape of defiant creatives and complicit bureaucrats. Most of all: definitely never comply with either of them. After all: it’s just a model.